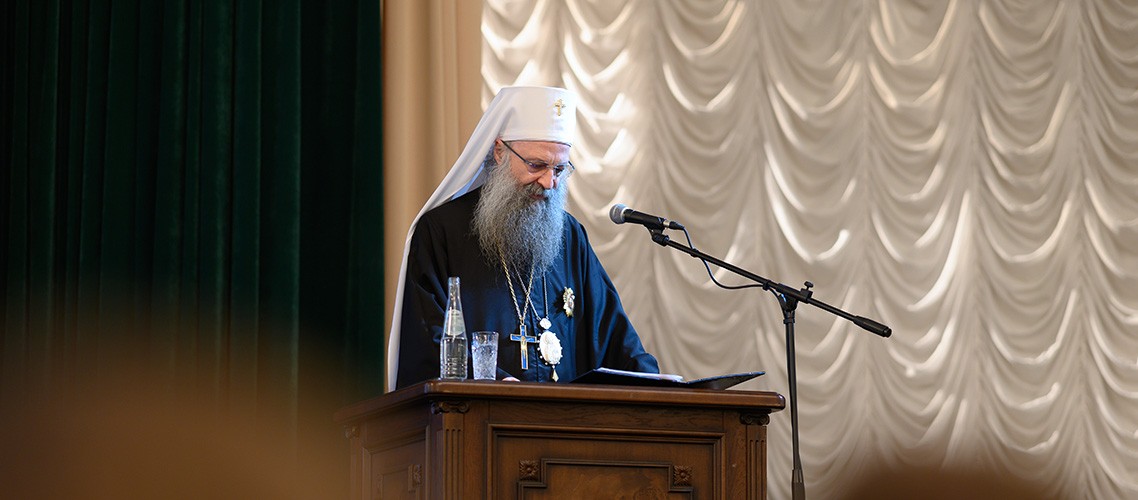

His Holiness Patriarch of Serbia Porfirije

Address by His Holiness Patriarch of Serbia Porfirije «On True Theology»

We present to your attention the address delivered by His Holiness Patriarch of Serbia, Porfirije, at the solemn ceremony of awarding His Holiness with an honorary doctorate from the Moscow Theological Academy. The address is preceded by words addressed to His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, the rector of MThA, Bishop Kirill of Sergiev Posad and Dmitrovsk, archpastors and pastors, professors, teachers, postgraduate students, students, and staff of the theological school.

Christ is Risen!

Your Holiness, Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia!

Your Grace, Reverend Bishop, Rector of the Moscow Theological Academy, Bishop Kirill of Sergiev Posad and Dmitrovsk!

Your Eminences and Graces, dear fellow bishops!

Most Reverend and Honorable Fathers, brothers and concelebrants in the Lord!

Reverend Professors and Teachers!

Dear Students and Postgraduates!

Beloved Brothers and Sisters in Christ!

With a deep sense of reverence, gratitude, and humility, I accept this extraordinary honor—the degree of Honorary Doctor conferred upon me by the world-famous and respected Moscow Theological Academy within the entire Orthodox oikoumene. I receive this award as one of the most significant milestones in my long-standing theological and academic-research activities, as well as in my pedagogical and educational service.

I accept this high honor not as a testimony to my own merit, but as an expression of the trust placed in me in service to the Divine Logos and the life of the Orthodox Church of Christ. I receive this award from the scholarly-theological community of the Russian Orthodox Church as a gracious gift and a visible sign of our unity in Christ—a sign that is at once obligating, inspiring, and strengthening.

That is why, first of all, I offer glory, worship, and thanksgiving to our Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Lover of mankind and Giver of all good things, the Son and Logos of God, the First and Eternal Theologian of the Church, who—by the good pleasure of the Father and the operation of the Most Holy Spirit, the Source of life and theology—has granted the human race the knowledge of truth and made us partakers in the Divine Mystery.

It is an honor for me to express sincere and profound gratitude to this honorable and God-pleasing institution—the Moscow Theological Academy—not only as a respected higher educational establishment, but also as a place of living Tradition and spiritual gathering. I recognize this spirit in the kindred mission of our oldest theological institution—the Orthodox Theological Faculty of the University of Belgrade, whose task is not only to preserve theological science but to enliven it in the life of the Church and the people.

We have gathered in an age that increasingly knows less of silence, stillness, and the word that matures in inner quiet. It is precisely in such times that the mission of preserving and renewing theological science compels us to remember that knowledge is not a mere accumulation of data, but a manifestation of inner maturity, a call to responsibility, and readiness to hear the voice of the other. In times of fragmentation and division, this event testifies that truth unites; that theology is not a dividing wall but a bridge that connects; that any true vocation—whether academic or spiritual—finds its fullness and meaning only in the Church.

Therefore, I thank you for the honor bestowed upon me, which is at the same time a call to more diligent service, more attentive listening, and more concentrated prayer. And now allow me to offer a brief theological reflection—not as a teacher, but as a Christian, a brother, and a co-minister, standing prayerfully before the Mystery of the Resurrection, on the topic “On True Theology.”

“If you are a theologian, you will truly pray, and if you truly pray, you are a theologian” (Εἰ θεολόγος εἷ, προσεύξῃ ἀληθῶς· καὶ εἰ ἀληθῶς προσεύξῃ, θεολόγος εἷ). This famous saying, usually attributed to Evagrius Ponticus, expresses a key insight of early Christian Tradition: theology and prayer are not separate endeavors or struggles but two modes of the same reality. When we speak here of prayer, we mean above all the confession of faith with the whole being—mind and heart—that the Divine Eucharist is the prayer par excellence upon which the life of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church is founded. Without participation in it—the Church’s All-Mystery—and without its imprint, it is not only impossible to theologize properly, but even to call oneself a Christian. Thus, the cited rule of our faith (lex credendi) indeed presupposes the rule of prayer (lex orandi); and the rule of prayer, arising from the Eucharistic ethos, gives rise to the rule of theologizing (lex theologizandi).

Returning to Evagrius’ saying, it is especially fitting to reflect on the relationship between prayer and theology in light of the Resurrection of Christ, which we joyfully celebrate in these days. For in the Risen Lord, the one who prays addresses not a concept or abstract ideal created by the mind, but the Living God, who by His death conquered death. Prayer becomes a dialogue with the Risen Christ, and theology—testimony to life that has triumphed over the grave. As the Apostle Paul exclaims: “that I may know Him and the power of His resurrection” (Phil. 3:10)—this is the inner longing of every true theologian.

This teaching, born of the spiritual wisdom of the desert fathers and later confirmed in the works of the holy fathers—such as Gregory the Theologian, Maximus the Confessor, Isaac the Syrian, John Climacus, and many others—reflects the deep unity of the human person before God.

Rooted in the Eastern Orthodox spiritual heritage, this saying affirms that theology is not merely an academic endeavor or intellectual discipline, but the fruit of direct, living communion with God. True theology arises not from abstract reflection, but from the stillness of the heart humbly standing before the Divine. True prayer means immersion in the mystery of God’s liturgical presence, and from this personal encounter is born the word that is worthy of being called theology (θεολογία).

This saying is far from just a spiritual aphorism. It has deep and far-reaching consequences—spiritual, ethical, ecclesial, even cultural. It unites the whole human being—mind, heart, body, and soul—in a single movement directed toward God. In light of this, theology is not merely speech about God, but a manifestation of an inner life transfigured by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

Therefore, this ancient maxim is not only a spiritual encouragement but a comprehensive theological vision that fundamentally transforms the very foundations of how theology is understood and how it manifests in life. From this starting point flow many profound and essential consequences.

On Theological Consequences

The aforementioned statement essentially affirms that true theology arises not from abstract speculative reasoning, but from personal spiritual experience. By «personal,» we do not mean individualistic, but ecclesial experience — one that is in harmony with all the saints. Theology, in this sense, is not primarily an academic enterprise but the fruit of an encounter, an existential and liturgical relationship with the living God. Prayer is not a preparation for theology — it is theology. In prayer, the person stands before God not as an observer but as a participant in the Eucharistic Mystery of God. This participation (méthexis) is the foundation of all genuine theological knowledge.

This understanding prioritizes experiential knowledge over intellectual abstraction. Authentic theological knowledge is holistic: it engages not only the intellect but also the heart, the will, and the purified nous — the mind transfigured by grace through ascetic effort (askesis) and humility. In this light, theology is only possible to the extent that the human person is continually transfigured. It is the path of theosis (deification), through which the one who prays becomes like God and thereby capable of perceiving divine realities.

This view also underscores the inseparable unity of orthodoxy (right belief) and orthopraxy (right practice). Right faith and right worship, doctrine and ascetic struggle, teaching and prayer are not parallel streams but one and the same path of communion with the Lord. Therefore, a theologian is not only a thinker but a witness (mártys) — someone who speaks about what he has seen and come to know in personal encounter. In this sense, theology is inherently liturgical and doxological. Its natural space is the Church’s worship, and its highest expression is the Divine Liturgy.

As the Apostle John testifies, “we speak of what we know and bear witness to what we have seen” (John 3:11). So it is with the theologian: that which is known and seen in prayer becomes theology.

The transforming nature of prayer reveals another essential aspect of theological authenticity: the correspondence between life and word. One cannot speak truly of God while living in falsehood. Theological speech severed from humility, obedience to the Church and her canonical ministers, and separated from repentance and love, loses its foundation. Prayer rooted in fidelity to the Church becomes a form of resistance — a refusal to accept the egocentric and shortsighted logic of this world and a quiet but firm opposition to forces that aim not at communion but control.

Such a theological vision protects against reductionist and secularized interpretations. It challenges modern tendencies that reduce theology to historical analysis, sociological commentary, or the construction of abstract conceptual systems. Instead, it insists on preserving theology’s mystical and mysterious nature as a mode of being — a relationship with the Holy Trinity and with one’s neighbor. In this context, theology must be interpreted through what could be called a “hermeneutics of humility,” where the interpreter is first and foremost one who prays, and only then one who speaks.

This, of course, does not diminish the value of academic research. On the contrary, it affirms and elevates it — provided it is rooted in a life of prayer. Careful interpretation of Holy Scripture, diligent study of patristic tradition, and critical thinking undoubtedly occupy an important and irreplaceable place — but they must be connected with an inner life transfigured by the grace of the Holy Spirit.

Thus, theology is not only speech about God — it is conversation with God. It is dialogical, relational, participatory. It is not a separate undertaking or enterprise but a mode of being — a life continually transfigured into the likeness of Christ. This is why the greatest theologians in Church history were first and foremost people of prayer — individuals whose words carried weight because they emerged from silence before the Mystery of Christ.

The statement about the relationship between prayer and theology becomes both a criterion and a corrective, exposing all forms of theological expression that are divorced from spiritual and ecclesial life. It calls for authenticity in faith and reasoning, for congruence between the subject of study and one’s way of life, and reminds us that possessing a diploma, academic degree, or title is not enough to be a theologian. One must kneel before the Throne of God and, in that humility, utter a word that transforms.

On Cultural Consequences

The consequences of this patristic statement go far beyond the personal or spiritual domain, extending from the inner chamber of the heart to the very heart of culture. If theology is rooted in authentic prayer, it does not remain an exclusively private spiritual endeavor, but begins to shape the imagination, value systems, and life patterns of a people. It becomes culture-forming in the deepest sense of the word.

In a world increasingly marked by noise, haste, and utilitarianism, the theological vision described above affirms the value of contemplation as a form of resistance to the modern secular cultural matrix. It reclaims silence, humility, and inner attention as higher forms of wisdom. In doing so, it challenges cultures obsessed with productivity and control, instead calling for a mode of being grounded in trust, humility, and communion.

In this understanding, theology is not merely the transmission of theoretical content — it becomes a formative factor. Theology represents a spiritual paideia (formation), an inner process of education, whose foundation lies in the lives of the saints, the rhythm of liturgical worship, the patient, gradual labor of prayer, and the careful study of sacred theological texts. Thus, authentic theologizing does not arise from data accumulation but is formed through a transfiguring encounter with God and with others. It is lived and transmitted in community — through common prayer, life in the sacraments, and the conciliar memory of the Church.

Culture naturally flows from this spiritual core. Icons, hymnography, liturgical poetry, and sacred architecture are not decorative embellishments or empty ornamentation, but living expressions of theological vision. Flowing from prayer, they invite others to participate in it. They confirm the words of St. Dionysius the Areopagite, who described the cosmos as a theophany — a revelation of the divine through the visible. The beauty of these cultural forms is not “aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake.” It is mysterious: revealing the invisible through the visible, the eternal through the temporal. In this sense, theology rooted in authentic prayer contributes to cultural renewal. It resists the degradation of the sacred, the reduction of theology to rhetoric (technología lógou, or logotechnía, in the words of St. Gregory the Theologian), and the reduction of education to narrowly professional training. Such theology calls for the revival of a mystical aesthetic, for a renewed discovery of language that is poetic, liturgical, and mystical. It restores a liturgical cosmology, in which the rhythm of time, the form of space, and the community itself are transfigured by the Holy Spirit and directed toward the Divine.

Moreover, this theological vision strengthens generational continuity. Prayerful theology makes possible the transmission of faith not only as instruction but as living experience — in stories, actions, customs, and sacred memory. It becomes the hidden architecture of a people’s cultural identity, rooted in something far deeper than ideology or sentiment.

This theology is by its nature both ethical and communal. It inspires authenticity in human relationships, encouraging sincerity, empathy, and integrity. In a world of simulation and performative interaction, it calls for depth, truth, and real presence. In being so, it becomes the foundation for genuine social renewal — not through programs and strategies, but through faces transformed by prayer.

In the broadest sense, this spiritual anthropology gives rise to a new vision of the world itself. Nature is no longer seen as raw material for consumption but as a sacred gift. Consequently, prayer gives rise to cosmological responsibility, and the spiritual life becomes the foundation for the preservation of creation — a humble care for it and its rediscovery as a manifestation of Divine wisdom and creative Mystery.

In cultures increasingly alienated from the transcendent, this ancient patristic insight remains a prophetic voice. Resistance to secularization should not take the form of escape or retreat but of a quiet return to the deepest sources of meaning. This thought reminds us that theology cannot be confined to classrooms and lecture halls or limited to the walls of churches — it must shape art, education, language, and political life (in its original, state-forming sense), as well as family and communal life.

A culture shaped by prayer is a culture not of power, but of peace; not of efficiency, but of beauty; not of control, but of gathering and communion.

On Social Consequences

If theology born of prayer is capable of transforming personal life and culture, then its consequences for society cannot be any less profound. Such theology offers an alternative vision of social order — a vision grounded not in power, profit, or utility, but in holiness, virtue, and spiritual authenticity.

At the heart of this vision is a radical rethinking of wisdom and authority. A true theologian, according to an ancient maxim, may come from any social background and be of any profession, provided their heart is oriented toward God in true prayer. This transcends social distinctions and challenges conventional social hierarchies and stratification. In societies marked by inequality and fragmentation, prayer becomes the measure of true equality — a bridge enabling any person, regardless of external status, to partake in divine wisdom.

Such a vision implies that authority arises not from coercion or power, but from the depth of human communion with God. This kind of authority becomes compelling not by being imposed, but by being received, emerging not from display but from silence. It is precisely this unforced, prayer-transformed authority that the Church offers to the world — a theological witness rooted not in domination but in grace.

At the same time, prayer is not an escape from the world, but an encounter with its deepest needs and wounds. To pray truly is to bring others before God. A theologian who prays does not retreat into personal piety, but becomes sensitive and responsive to the suffering of others. Compassion becomes inseparable from contemplation. In this context, true theology becomes a prophetic voice — speaking truth to power, defending the poor, and exposing injustice not through ideology but through mercy.

Communities nourished by liturgical prayer become communities of solidarity and mutual belonging. Theology ceases to be individual speculation and becomes a shared mode of being. Liturgy becomes a school of justice, peacemaking, and integrity. In such societal frameworks, prayer does not foster passivity, but encourages ethical vigilance: it teaches the Christian to see the image of God in every person, and in every action the eternal consequence before the face of God.

Theology born of prayer resists the dominant narratives of modernity: it offers an alternative to technocracy, affirming that wisdom cannot be reduced to data, expertise, or sheer efficiency; it exposes consumerism, calling instead for a culture of simplicity, interior life, and moderation — in contrast to exploitative productivity and acquisitiveness; it questions superficial activism, emphasizing that action must be rooted in contemplation, and justice in the grace of the Holy Spirit.

Above all, it offers an integrated vision of human growth, in which body, mind, emotions, and spirit are united in a single movement toward God. In light of this, theology does not critique the world from the outside, but seeks to transform it from within — from the heart of the person, through culture, to the very foundation of social structures.

To live according to this vision is to confess a reality deeper than politics, stronger than ideology, and more enduring than any kingdom of this world: the Kingdom of God is already present in the Eucharistic assembly of the Church, in the hidden life of the saints, in the silence of true prayer, and in the witness of those whose theology has been forged in the fire of God’s love.

Theology as Life with God

From the ancient patristic saying does not emerge a definition of theology in academic terms, but a vision of theology as a way of being — a life lived with God, in humility, prayer, and love. It is a call to renew the understanding of theology as life-in-communion — a way of life expressed in word, thought, action, and culture.

In a world divided between intellectualism on the one hand, and superficial activism on the other, the patristic maxim calls for a reunion of spiritual depth with responsibility, of commitment to the Church with engagement in the world. A true theologian does not retreat into private piety, nor dissolve into ideological noise, but stands — prayerfully — at the intersection of heaven and earth, presenting the world before God. As St. Gregory the Theologian testifies, one must indeed first be purified and only then enter into conversation with the Pure One (Oration 27: δεῖ γὰρ τῷ ὄντι καθαρθῆναι πρότερον, εἶτα τῷ καθαρῷ προσομιλῆσαι). Accordingly, the true theologian is not merely one who thinks about God, but above all one who lives with God.

This vision offers a transformative alternative to both individualism and collectivism. It affirms that true societal renewal begins not through systems of governance, but through transfigured persons — those whose hearts have been formed by the love of God. Such a person becomes a bearer of light not through domination, but through kenotic witness, imitating Christ, who prayed in Gethsemane and in silence offered Himself in sacrifice upon the Cross.

Therefore, theology is not a specialization, but a vocation; not a privilege of the few, but a calling addressed to all who truly stand before God in prayer. It demands not only study, but transformation — spiritual, ascetic, and liturgical. If theological institutions are to remain faithful to this vision, they must prioritize not only intellectual achievement, but the sanctification of the whole person. Prayer must not be an ornament of a theologian’s life, but his method, his breath, and his rhythmic heartbeat.

At the center of this vision lies a renewed Christian anthropology: the human being is not primarily a political or economic creature, but a liturgical being (homo adorans). In prayer, the human person becomes what they are called to be — a living icon of Divinity, participating in the being of God through grace and the Sacraments.

Such theology offers a quiet yet powerful answer to the weary logic of the modern age. It rejects the secular division between the sacred and the secular, the spiritual and the rational. It sees truth not as an abstract proposition, but as a Person — the Risen Christ, in whom the Church lives through liturgical communion and prayerful assembly.

Theology as the Guardian of Human Dignity in Times of Ideological Simplifications

Thus, theology demonstrates its ability not only to elevate the soul and mind, but also to purify the collective consciousness of communities misled by ideological simplifications. Indeed, the theological vocation should be recognized as a safeguard against any form of reductionism. The phenomenon of ideological reductionism often arises when dichotomous moral frameworks are adopted—those that place sociopolitical reality into rigid categories of good and evil. This oversimplifying approach reflects certain anthropological constants inherent in the fallen state of human nature, especially social patterns that have developed over centuries to ensure so-called collective security.

At the root of this fallen way of understanding existence lies a primordial inclination toward binary classification—the division between the familiar “we” and the different “they.” In this sense, self-identification is formed through a dialectical process in which the presence of the “other” becomes a necessary counterpoint for self-understanding: whiteness implies blackness as its conceptual opposite; Western identity requires the Eastern as a necessary counterbalance; civilization presupposes barbarism as its antithesis; democratic values are affirmed in contrast to supposedly authoritarian systems. This pattern reveals that moral self-awareness is often built on contrast: one’s own goodness becomes intelligible only when it resists a perceived evil.

Ideological systems further intensify these postlapsarian cognitive tendencies, reinforcing tribal divisions and differentiations. Such interpretations give rise to two simultaneous distortions of reality: an excessive emphasis on intragroup similarity and an exaggeration of intergroup differences. Manichaean interpretative frameworks create strong cohesion within a community, supported by a self-affirming narrative in which one’s own group represents the embodiment of moral integrity, while the other side appears as the personification of moral corruption.

History is replete with testimony of the suffering of communities caused by violence stemming from such ideological and dualistic constructs. This tragic reality—so familiar to the Russian and Serbian peoples—points to the vital importance of authentic theological discourse, not as an empty academic exercise, but as a life-giving preservation of faith, cultural heritage, and national identity. When properly understood, theological reflection becomes a guardian of the fullness of human, national, and Christian dignity and identity.

This is why the ancient Christian maxim—“If you truly pray, then you are a theologian”—is not merely a spiritual aspiration but a prophetic commandment. It calls for a theology that transcends factionalism, halts polemics, and becomes a space of encounter—not of conflict, but of communion; not of possessing truth, but of participating in the Truth, which is Christ Himself.

In this context, knowledge ceases to be an act of distant domination and becomes a humble participation in Divine being. As the Apostle Paul testifies: It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me (Galatians 2:20). Such theology begins not with assertion, but with silence; not with debate, but with worship.

This saying is not merely a mystical proverb intended for monks. It is a comprehensive vision of Christian existence—a vision for education, governance, cultural renewal, and public life. It calls theologians to become saints, and saints to become theologians. It dismantles the false dichotomies of contemplation and action, faith and reason, Church and world.

Final Thoughts: Theology as Witness to Unity and Love in the Light of the Resurrection

Furthermore, this patristic principle—that only the one who truly prays is worthy to be called a theologian—serves as a safeguard against elitist tendencies in Church life. It undermines any inclination toward theological self-exaltation and the absolutization of personal opinions, which, when detached from prayerful discernment and ecclesial humility, can become seeds of discord.

Theological elitism represents a subtle yet real danger to the preservation of ecclesial unity, especially when it manifests in rigid personal stances placed above the living Tradition of the Church. However, authentic theology, rooted in prayer and the Eucharistic community, nurtures humility, openness, and the capacity to listen—to God, to the Church, and to one’s neighbor.

In light of this, the connection between prayer and theology is not only a sign of spiritual maturity but also a guardian of the unity of God’s Church. This connection preserves the unity of the Body of Christ, reminding all who speak about God that their words must be born in the fear of God, in reverence before the Mystery, and in love for the Church.

In the radiant light of the Resurrection, we remember that true theology is not a system to be mastered, but a life to be offered to God. A theologian is not merely a knower of Divine reality, but a participant in Divine being—one who prays to the Risen Christ and is formed in love according to His image. As proclaimed in the apex of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom:

“Let us commit ourselves and one another,

and our whole life

unto Christ our God.”

In this Eucharistic tradition, theology reaches its fullness—not in speculation and discourse, but in offering. For in Christ, Risen and Glorified, every word finds its truth, and every silence its meaning. Thus, we proclaim:

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

Therefore, let every theologian be first a witness to this Paschal Mystery—not only in word, but in heart; not only in thought, but in a life transfigured by the light shining forth from the empty tomb.

In conclusion, allow me once again to express my most sincere gratitude for the great honor bestowed upon me. I receive this gift of love with humility and joy—not as a personal triumph, but as a testimony of your trust in the Church I serve and in the common mission we share before the Lord.

I extend my most heartfelt and brotherly wishes to His Holiness, Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia. May the Lord grant him many years of wise pastoral and patristic leadership of the sister Russian Orthodox Church—for the spiritual flourishing of the beloved Russian people, for the strengthening of our common Orthodox witness, and for the deepening of our mutual respect, God-pleasing cooperation, and all-encompassing communion in love.

To all the faithful clergy, monastics, and laity of the Russian Orthodox Church, I send my warmest greetings and sincere prayerful wishes. And to the entire Russian people—a people of profound spirituality and confessional courage—I offer every good wish of peace, prosperity, and God’s blessing.

I thank the Lord and your love for this honor, which I now joyfully share with the faithful people of the Serbian Orthodox Church, whose warmest greetings, sincere prayers, and Paschal congratulations I convey to you in the joy of the Risen Christ.

Christ is Risen!